In this exchange of questions between myself, Ellen Mueller, and Genie Hien Tran, we reflect on the exhibition, Teo Nguyễn: Giấc Mơ Hòa Bình [Việt Nam Peace Project]. This show is on view July 30, 2022 – June 18, 2023 in Galleries 262, 275, and 280 at Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Teo Nguyễn, “Phan Thị Kim Phúc” (2018) Acrylic on vellum, mounted to aluminum

EM: When and how to provide context seemed like a question the artist made careful decisions about. I wondered what you thought about what was and was not provided?

GHT: Talking about the paintings specifically, I think the majority of them don’t provide much of what their sources are, such as the original photographs and other researched materials. They only provide the artist’s perspectives. This to me is interesting. Growing up Vietnamese, I refer to the war as “The American War” and it is of course the opposite here. The difference is a matter of perspective, the point of view of who the speaker is. I believe that by stripping away context, the artist is revealing to us his point of view instead of what was provided to him. Nguyen is choosing to see what he would like to see; and in his words, it is worthiness, beauty, reconciliation, resistance and spiritualism. On the other hand, the artist purposefully chooses to reveal the source such as “The Terror of War” photograph for one of his paintings. By doing this, he’s emphasizing the story of the girl in the photo, Kim Phúc, who most often referred to as the Napalm girl. In the didactic, he gives space to show her hope, her fight and commitment to live. Through her story, I believe Nguyen finds the power of resistance.

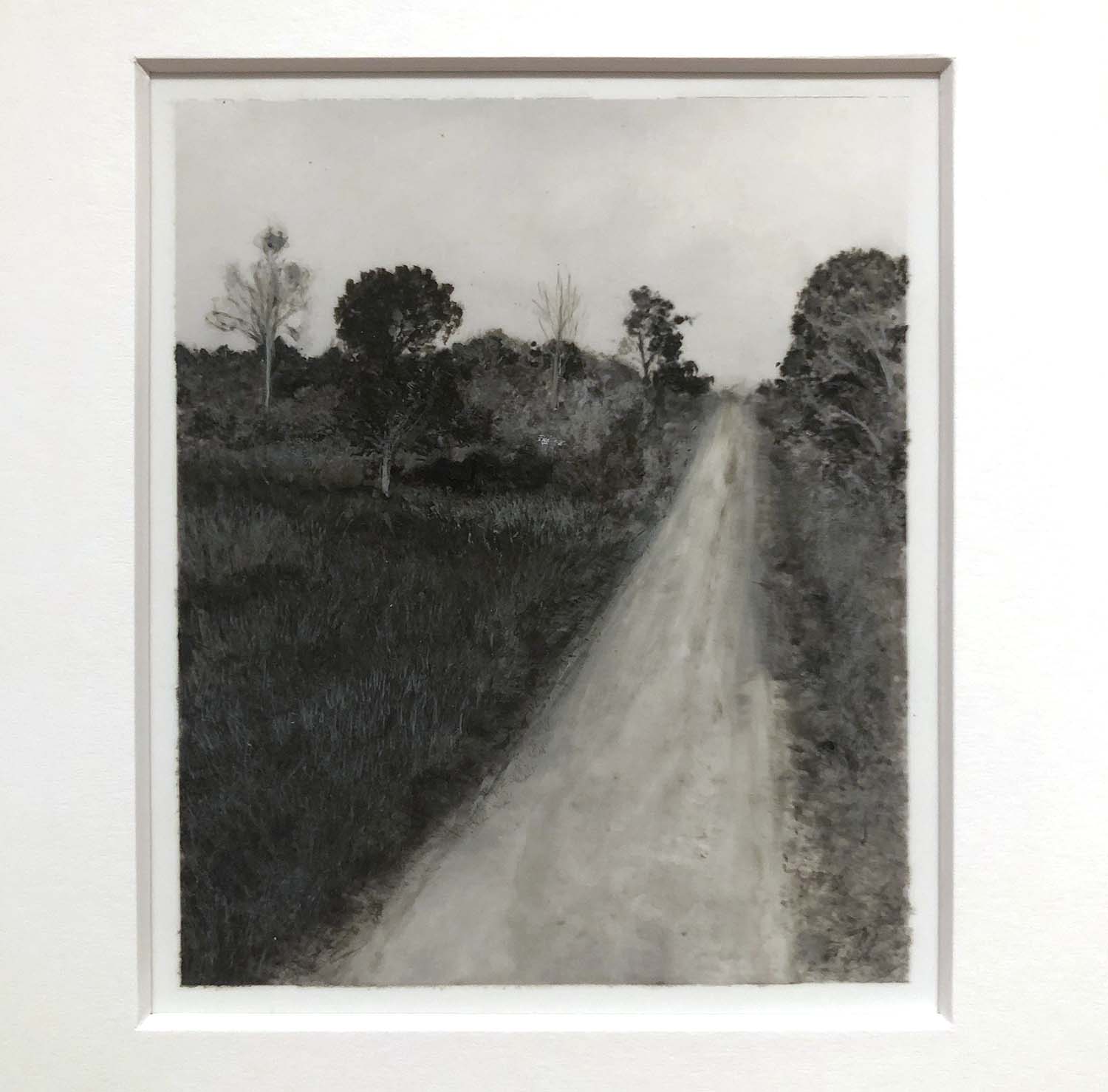

Also, even though I understand that the paintings must have been of real places and regions in Vietnam, there are no indications of street name, town, village and land marker that would lead me to a specific location. Without such information, you as the audience are trusted to view the work solely through the artist’s point of view—through his colors, language, and brush strokes, etc. Even without reading the artist’s statement, one could sense peacefulness, and at the same time, sorrow and mourning through the paintings very effectively.

Teo Nguyễn, “Agent Orange” (2022) archival aqueous pigment prints on transparent film; acrylic

EM: The scale shifts in this exhibition are significant, from tiny and large-scale photorealistic paintings, to the video work, to the huge installations hanging in the atrium or installed on the floor. I see similar scale shifts in your own practice, with tiny images and collaged moments arranged within much larger fields or picture planes. I wondered if you had any thoughts on the use of scale?

GHT: I know I mentioned this in the question I posed for you, but this exhibition makes me think a lot about the body. I think it has something to do with the constant overlaps of what is and isn’t seen, shown or provided. From the paintings which have war and human evidence deliberately removed to the floor paper installation of dead and missing Vietnamese people, this exhibition is empty of bodies. Contrasting that with the different scales of the work, which I feel require the viewers to compose their body differently depending on the piece: slouching down and peering into his mother’s intimate poetry, or tilting their heads back to look at the ceiling installation. I’m not sure entirely what this shift in movement means to me, but I find that it’s interesting to actively move yourself around and activate many senses in order to be immersed in an exhibition that is mostly of missing and lost bodies. I also think it almost goes back to the idea of forced perspective, of point of view. With the many different scales, the artist is making us ask questions of: Why is this scene at this scale? Where do I stand to experience the piece? What do I miss and gain from my way of seeing?

The scale shift in my own work is different in my opinion. I think Nguyen sees each of his paintings or pieces as a totality, while I think my images are part of one another. When I shift the scale of an image, it is because they either become more or less visible to me in the moment, and are completely dependent on its relationship with other images. However, sometimes I structure my images and their scales entirely based on technicality or spiritual reasons. If a scale or composition makes me feel good, I’ll work with that and won’t impose too much thinking behind it.

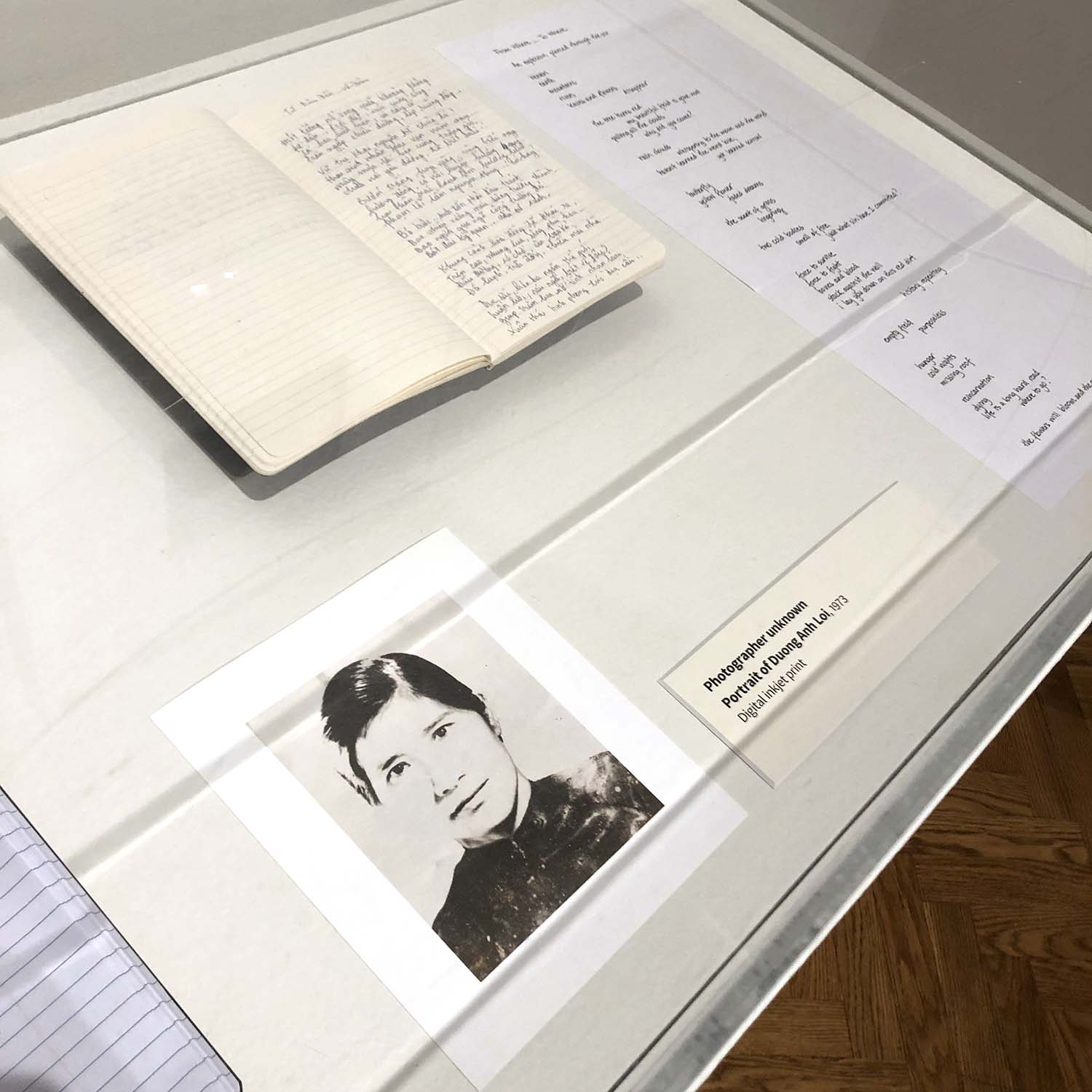

Poetry and photo in display case in Teo Nguyễn exhibition; photographer unknown for Portrait of Duang Anh Loi (1973), digital inkjet print

EM: Point of view, memory, and familial relationships are important to the conceptual underpinnings of these works, from the photojournalist’s perspective to the artist’s mother’s reflections. Did anything related to point of view stand out to you?

GHT: Feel like I touched on that a little with the other answers. There definitely is a strong undertone and influence of memory and familial relationship alongside his point of view. In the video and poetic piece, we see a much more personal take at the war and how it affected the artist’s familial relationship. These are one of the only few pieces in the show with presentations of a person, and both are of his mother (or echoes of her image, language, etc.). With both, we get this sense of loss and separation that are a lot more obvious and pungent. Accompanied with no dialogues, the song in the video piece reminded me of a lullaby a mom would sing to her young child. The melody also lingers with you when you are reading the artist’s mother’s writing due to the pieces being next to each other. To me, the memory of the artist’s mother and his familial relationships feel like a cornerstone, a grounded starting point in order for him to venture to other viewpoints.

Teo Nguyễn, “We Never Met, Yet Our Souls Embrace, Yêu Nhau Trong Phận Người ” (2018) acrylic on vellum, mounted to aluminum

GHT: When approaching the topics of war and human trauma, the artist deliberately removes human depiction and historical evidence and yet, to me, it seems that the land somehow remembers the pain. How does the mere appearance of land and environment make you feel as the audience? What do you think of the idea of land storing memories and if you have anything more to add to that?

EM: The painted landscapes are beautiful on their own and the absence of the horrors of war make that beauty all the more poignant to me because it underlines the total unnecessary-ness of that violence. The space thrived before the war, and while the land will continue to hold memories of the violence via depressions and clearings in the brush, it will also slowly return to these pre-war states. I believe the time it takes to heal the land, letting plant and animal life do the slow work of mending, is a long-term reminder of the harm done.

Teo Nguyễn, Remembering Other (2022) stacked white paper; transparent acrylic; site-specific installation

GHT: As you mentioned, the work ranges from 2-dimensional drawings to video work and ceiling installation. Though they might be different in format and scale, in each piece, there is an implication of the body—not only of the dead and wounded but also of the artist. I wonder if you thought of this as well and what are your thoughts on the hidden bodies behind the work?

EM: I observed a sense of hidden bodies most intensely with Remembering Other, which consisted of stacks of white paper in transparent acrylic boxes, physically illustrating the scale of loss of life on behalf of the Vietnamese people, both military and civilian casualties. There were also paintings that implied hidden bodies to me, but much more subtly via the compositional choices.

Teo Nguyễn, The Singing Stops in All the Trees, Hát Trên Những Xác Người (2016) acrylic on vellum, mounted to aluminum

GHT: Translation is used thoughtfully throughout the entire exhibition. However, from my understanding of the Vietnamese language, the translation is loosely connected and leaning more poetic rather than precise. (For example, The Singing Stopped in All the Trees isn’t exactly a one-to-one translation for the title Hát Trên Những Xác Người, which translated literally to To sing on top of bodies). Along with the artist’s mother’s poem display, language seems to wield as much power as visual in the exhibition, and I’m curious what you think about the role of language, translation, and written text when paired with visual art.

EM: First, I feel lucky to get your insight here as a speaker of Vietnamese. The difference in translations is stark, and illustrates just how much power the translator wields. Having both written material and visual art side by side in this case helps highlight how each medium has its own strengths in different ways. Sometimes the specificity of words seem more decisive and pointed, directing the viewer/reader to exactly what the artist/author wants us to observe. In contrast, at other times the image is most impactful because it shows us, rather than describing what we should pay attention to. Each viewer translates those images based on their personal context, whereas with the translated text, some conceptual choices are made for us.

Further discussion in the video below:

Disclosure: I know Genie Hien Tran as a past student when I was directing the MFA program at MCAD.